Nocycle is an open source library that started with a desire to make a data structure that could store a directed acyclic graph in a somewhat minimized adjacency matrix format. It can work with over 216 vertices. This is beyond what can be achieved on 32-bit architectures with the Boost Graph Library adjacency_matrix...which in my tests on gcc 4.0.1 stopped working after around 12,000 vertices.

As an additional thought experiment, I decided to try getting the DAG to keep a cached sidestructure of its own transitive closure. Though this goal has been achieved, more clever methods will be needed to make it palatable for use on large graphs where edge insertions and removals are frequent. So by default, caching is disabled and Nocycle uses a depth-first-search when reachability needs to be calculated (such as to prevent inserting a link that would cause a cycle).

Though really only an exercise at this point, I didn't see why I shouldn't put this out for others to use or peer-review. So the code is released under the Boost Software License. This permits liberal inclusion in both open source or commercial software, and I welcome comments or improvements. You can download it from GitHub, or just browse the source:

Note

The current choice of public inheritance vs. private inheritance vs. composition is driven completely by expedience. What role virtual methods will play needs to solidify, as well as what the best directions would be to build a storage class compatible with the boost templates.

The rest of this page I'll devote to explaining the implementation.

Compact Representation

The way Nocycle stores its graph data is as an adjacency matrix. However, it's more compact than people typically bother to write. Let's start by imagining we are using an adjacency matrix for just 3 vertices (V0, V1, V2):

| V0 | V1 | V2 | |

| V0 | .. | B1 | B3 |

| V1 | B2 | .. | B4 |

| V2 | B5 | B6 | .. |

Excluding connections from vertices to themselves "..", we need six binary bits (B[n]) which indicate whether a directed edge exists. There are two independent bits for each vertex pairing in the set, one for each direction. For instance, B1 tells us if V0 points to V1 (V0 → V1), while B2 tells us if V1 points to V0 (V0 ← V1).

However, if we are working with a directed graph that specifically prohibits cycles, we don't need two fully independent bits to encode the relationship between a pair of vertices. This is because V[x] → V[y] and V[x] ← V[y] are mutually exclusive, and allowing such connections would create an instant cycle! So for each pairing of vertices, we only need a tristate:

| V0 | V1 | V2 | |

| V0 | .. | T0 | T1 |

| V1 | XX | .. | T2 |

| V2 | XX | XX | .. |

Where before we needed six bits, we now have three tristates (T[z]), each of which can hold one of these possibilities:

- s0: no connection

- s1: lower numbered vertex points to higher numbered vertex

- s2: higher numbered vertex points to lower numbered vertex

This representation saves us from accommodating states where vertices both point to each other. Generally speaking, you'll need half as many tristates as you'd need bits...and a tristate needs slightly less than two bits to be represented. It's an approximately 20% space savings, and you can see the Nstate library for some generalized helper classes that I wrote to make this transparent to the graph code layer.

I wanted to allow for fast dynamic growth... from just a few vertices to thousands. For this reason, the cells are mapped into positions in a linear tristate array such that the connection information for higher numbered vertices appears after all the data for connections between lowered numbered vertices. Therefore a scheme that works for K vertices can be resized in place for K+δ or K-δ vertices without disrupting the existing data.

It is still possible to represent cyclical graphs in this format, so not all encodings will be valid DAGs. The broader class of what we are capable of representing are something called oriented graphs. From Wikipedia:

The oriented graph, is a graph (or multigraph) with an orientation or direction assigned to each of its edges. A distinction between a directed graph and an oriented simple graph is that if x and y are vertices, a directed graph allows both (x,y) and (y,x) as edges, while only one is permitted in an oriented graph.

So in Nocycle, I implemented the class

DirectedAcyclicGraph using the foundation of a class called OrientedGraph (which, in turn, is implemented on top of NstateArray!)Note

The usual caveats for an adjacency-matrix based implementation apply! Getting its list of incoming or outgoing edges involves searching all slots paired with other vertices. So regardless of how many connections a vertex has, the cost associated with getting the full list is proportional to O(V)...where V is the number of vertices in the graph. Answering the question about whether any specific linkage exists is still O(1).

Tracking Vertex Existence

Boost.Graph's

adjacency_matrix does not currently implement boost::add_vertex or boost::remove_vertex. More generally, boost graphs always have a number of functional vertices equal to their current capacity. So although you can have a vertex with no incoming our outgoing edges, you can't have a descriptor in your vertex in your graph which "does not currently exist".

Nocycle can "push" and "pop" vertices at the end of the store, and deleting vertices in the middle opens up a space that can be reused. To assist in managing currently unused vertex IDs, an additional tristate per vertex is folded into the memory layout to track its existence. This revised organization for 4 vertices shows the tristate indexes and whether they are (C)onnections or (E)xistence for the pertinent vertices:

| V0 | V1 | V2 | V3 | |

| V0 | E0 | C2 | C5 | C9 |

| V1 | XX | E1 | C4 | C8 |

| V2 | XX | XX | E3 | C7 |

| V3 | XX | XX | XX | E6 |

Now we have an array T[] which contains both the existence tristate E (with an unused state) and the connection tristates C. We need the function E(N) where T[E(N)] is the existence tristate for vertex N. Also, we need C(S,L) such that T[C(S,L)] is the connection tristate for V×S and V×L (where S < L).

First, E(N) is easy. It's the sum of the first N natural numbers:

E(N) => N*(N+1)/2

A slight tweak will give us C(S,L) for the connection between a smaller numbered vertex and a larger one:

C(S,L) => E(L) + (L - S)

This way we have a growth model that lets us encode existence and connectivity in a linear series of tristates, that can expand and shrink. I elected to use the extra state of the existence tristate as a second "vertex type"--so all vertices that exist may be either

vertexTypeOne or vertexTypeTwo.Reachability Calculation

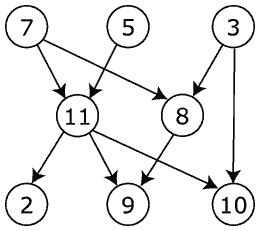

An important question for a directed acyclic graph is whether one vertex can reach another by following a path of edges along the direction of the arrows. To get an idea of what that means, let's imagine you have a graph like this one (from Wikipedia):

- "Can Vertex 7 Reach Vertex 10?" Yes: by going via Vertex 11

- "Can Vertex 9 Reach Vertex 8?" No: arrow points the wrong way

- "Can Vertex 3 Reach Vertex 5?" No: no path connects them

Answering this question is particularly useful for determining if it is safe to insert an edge into the graph without creating cycles. To see this is the case, imagine making an edge pointing from Vertex 2 to Vertex 7 in the graph above. This would create the cycle 2→7→11→2...but it would have been avoidable if you had realized that 7 "canreach" 2 prior to making that link!

Most programs use search algorithms to answer questions of reachability, and those searches slow down as the number of vertices and/or edges increase. A depth-first search is a common approach, which has a time complexity of O(V + E) and a space complexity of O(V). This is the default implementation for computing reachability in Nocycle. It should also be noted that when you account for the overhead of querying the adjacency-matrix to get the list of connections for a given vertex, the O(V) performance of that operation gives rise to an effective time complexity more like O(V2) (!!)

The flag

DIRECTEDACYCLICGRAPH_CACHE_REACHABILITY tries to cache the transitive closure to provide O(1) answers to reachability. A compact graph representation mitigates the fact that storing the transitive closure alongside a graph effectively doubles its size. (Nocycle can hold a 4 vertex graph and its transitive closure in just 64 bits!) Unfortunately, keeping the transitive closure in sync on a volatile graph is computationally expensive. :(

To see this, imagine performing an insertion from fromVertex→toVertex. We know that all vertices that canreach fromVertex (including fromVertex!) can now reach toVertex, as well as anything toVertex can reach. We must union toVertex's reachability onto each member of the set canreach(from)...which for a graph with V vertices is an O(V2) time-complexity operation with O(V) space complexity. When you add in that merely getting the connectivity list for a vertex in an adjacency matrix is a significant O(V) operation, you're approaching an O(V3) worst case scenario.

Note

Building the transitive closure from scratch with the Floyd-Warshall algorithm is only O(V3) without the need for the O(V) operation of getting an adjacent vertices list. So when incremental maintenance has a worst case with the same upper bound as a full regeneration, there's cause for thinking carefully about whether the nature of the data and access pattern warrants invalidation.

Experimental Code

I tried a few techniques to improve performance on volatile graphs. For instance, I used the cache graph's

vertexTypeTwo to indicate when the outgoing reachability for that vertex might have false positives. This made it possible to defer the transitive closure update while still knowing something in the meantime (e.g. that if there wasn't an edge to a vertex in the reachability graph, then it still could definitely not be reached).

Also, I noticed that storing reachability links for vertices that were directly connected was somewhat redundant. After all, one can check for adjacency of V×x and V×y in O(1)...so performing that check prior to checking the reachability does not cost much. This made it possible to "reclaim" a tristate for every edge in the main graph. If you enable

DIRECTEDACYCLICGRAPH_USER_TRISTATE, then this tristate becomes available for client use.

Once I had reclaimed this tristate for every edge for the user, I decided to try taking it back to see if it could add features to the cache. With the compile flag

DIRECTEDACYCLICGRAPH_CACHE_REACH_WITHOUT_LINK, then two of the three possible tristates are used to answer the yes/no question of "Could the vertex pointed to by this edge be reached even if the physical edge were removed." If that is true, then you know the link can be removed without propagating any further invalidation of the cache. It might be an interesting question for certain clients in its own right.

These optimizations don't do anything about the worst case performance, and don't help on volatile graphs. But at least they give a background process something to clean up that may accelerate certain operations. If there's a long wait between insertions and deletions, and a lot of reachability checks in the meantime...they could enable some interesting scenarios. The regression tests handle these variations, so regardless of whether they're useful--they work and can be kept working. :)

Further Directions

My attempt at caching the transitive closure was fairly simple and had the natural burden for maintaining such a cache. This is a general-application implementation, there is room for optimization on specialized cases where more is known about the data or access pattern.

One aspect that I found discussed in academic papers is leveraging the idea of "strongly connected subgraphs" to compute transitive closure efficiently. And if you know more about the nature of your graph--such as if it is sparse, or any other special properties, then "graph labeling" approaches are also used.

As I've read more about the Boost Graph Library, I see that one of the main reasons for its abstruse mechanics is to facilitate the application of its algorithms to custom data structures without loss of performance. It would be interesting to see an adapter developed that used

OrientedGraph as a store for applying to boost graph algorithms. Perhaps it could be called boost::adjacency_spiral, and bring about some of the missing resizability and scalability that boost::adjacency_matrix doesn't have for DAGs?

If you know of any other interesting ideas, post a comment or email me!